It’s hard to imagine a more intense period of rapid newsroom change than the early days of the pandemic last year, but this year’s gradual re-opening is posing significant challenges of its own. Rather than back to normal, it’s back to the future — a future that will require a new burst of innovation and one that local news leaders will help define.

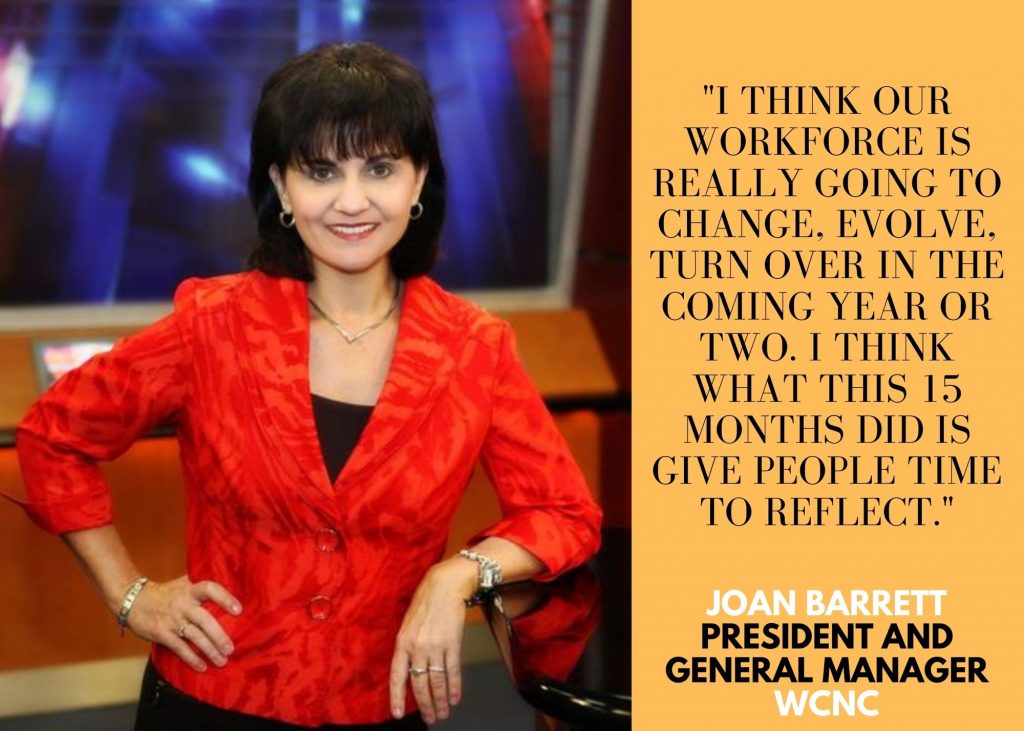

“I think people have used this year to have life-changing moments,” said Joan Barrett, who took over as general manager of TEGNA’s WCNC in Charlotte just three days before the pandemic lockdown in March of last year. “Like thinking about, do they want to work nights or mornings or weekends anymore? And do they even want to do this? And maybe they do want a full-time work-from-home job, and they’re pivoting to look for those opportunities. I think our workforce is really going to change, evolve, turn over in the coming year or two. I think what this 15 months did is give people time to reflect.”

In addition to her day job, Barrett is a faculty member of The Carole Kneeland Project for Responsible Journalism, a nonprofit organization that provides continuing education for TV and digital news managers. Some of the news leaders who have gone through the program have been meeting up virtually from time to time to compare notes.

Last week’s topic was “The Big Return.” I was allowed to listen in on the conversation, which was led by Kneeland executive director Stacy Baum. The participants stressed that they were speaking for themselves and not their corporate bosses, who will set the rules for the big return. But the issues these local leaders are now confronting will resonate in every TV newsroom.

Here are my five takeaways.

Local TV newsrooms deserve credit for an extraordinary job continuing to serve their audiences under extremely difficult conditions, but that drastic adaptation came with a cost.

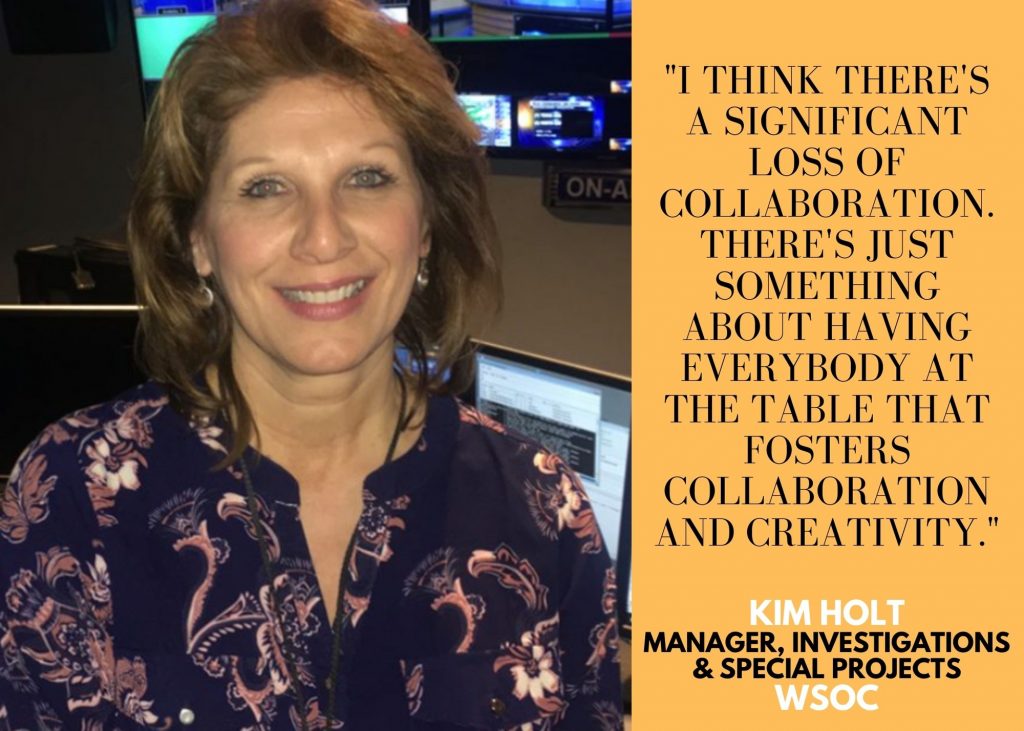

“I think there’s a significant loss of collaboration,” said Kim Holt, who runs investigations and special projects at Cox’s WSOC in Charlotte. “There’s just something about having everybody at the table that fosters collaboration and creativity. And despite your best efforts, you can’t replicate that through virtual meetings.”

“You didn’t get to walk the room,” said J Bates, news director at Scripps station KIVI in Boise. “There was no way to connect with people except through this thing [i.e. Zoom], which made change hard, because you couldn’t really reassure someone through a screen as well as you could at their desk.”

“I actually had a producer that had to bail on me about halfway through it,” said Nick Genty, news director at Sinclair’s KATV in Benton, Arkansas. “Because she’s like, ‘I miss being around [the newsroom]. And now it’s just a job.’ And I think we lacked a lot of that sense of newsroom camaraderie, where people can talk about things other than just work.”

Another COVID casualty: the in-person mentoring of young journalists. “I look at the rookie class of reporters as having gone through [an experience] kind of like how they talk about virtual school: how much was missed versus in person,” said John Laughrin, news director at Scripps station WGBA in Green Bay. “I think this whole last class of MMJs who came into the field in this last year are behind because they didn’t get to be a sponge and get to experience newsroom culture and grow and learn.”

“People who feel they have successfully been working from home are now wondering why they can’t continue to do so,” Joan Barrett said. “I think the challenge is that it’s as unique as people are unique. This person wants to come back and this person doesn’t. It is not one case fits all.”

Kim Holt pointed out that while some of her young producers can’t wait for everyone to return to the newsroom, “We have people who are very eager not to return, because they’ve been able to achieve a work-life balance through working from home and not commuting. I had a producer put it this way: ‘Working this way allows me to work my job around my life, versus working my life around my job.’”

“I really want producers back, because we’re having trouble with the collaboration thing. You know, Slack just isn’t cutting it for that,” said J Bates. “But here we are. The producers are like, ‘No, I kind of like my life — sitting at home writing the news.’”

“We’ve all changed,” John Laughrin said. “I know I’ve changed myself. My routines have changed, my patterns. So knowing that I have a little anxiety about going back and exactly what that’s going to look like, now I’ve got a whole team to lead through that. That’s what’s keeping me up at night; How are we going to work ourselves through this and get ourselves to the other side of what will be that new normal?”

Ownership groups are for the most part moving slowly as they set policy for returning to the newsroom, and with good reason (in addition to safety). On one hand, flexible policies about working remotely will be popular, especially with some employees. “It’s going to make it easier for this industry to keep working parents, specifically working moms, in a career where maybe they don’t feel like they have to leave because ‘I want to go have kids, I want to be able to do my job and also be there for my kids,’” said Ryan Robertson, news director at TEGNA’s WOI in Des Moines.

But Robertson also worries that some employees could take advantage of policies that are too lenient. “I think when you start going down the work remote route, we’re all assuming that the people who are going to be on staff are the highest character, best self-motivated people,” he said. “Everyone on my staff now, absolutely, they can work remotely, and they can kick butt doing it. Not everyone in my career that I’ve worked with would I say the same thing about.”

Michael Fabac, a Kneeland faculty member who oversees news for the News-Press and Gazette (NPG) stations, agrees that the balancing act can be tricky. “That’s something our company is struggling through: if it makes sense for a producer or an assignment editor to have some parameters set for when it is okay to be remote. One of our markets sort of went rogue, and we had people just going, ‘I’m working from home today,’ with no other explanation. That’s way too flexible. But does it make sense based on good performance and planning, and all of those other things that factor into the well organized newsroom, to set those parameters? I think it does.”

“Millions of people have spent the past year re-evaluating their priorities. For many people, this has become a moment to literally redefine what is work,” veteran editor Joanne Lipman wrote last week in TIME magazine.

In this post-pandemic moment, newsrooms will be struggling to manage a new set of expectations among their employees. J Bates thinks that for some, quality of life issues will alter the traditional trajectory from market to market. “Our philosophy on recruiting needs to change,” he said. “Nobody’s climbing to get to New York. They’re climbing to get to where they want to live.”

“The competition for people right now is really, really stiff,” said Melissa Luck, news director at Morgan Murphy Media’s KXLY in Spokane. “And I think a lot of people emerged wanting to do something different or wanting to get closer to home. Some people [used to say] ‘Eventually, I want to get closer to home.’ I think after the last year, people want to be close to home now.” Adding to the challenge for small and mid-size stations, Luck said, is that bigger markets are now hiring people “with way less experience.”

Some of the news leaders were reluctant to speak for attribution about pay scales given corporate sensitivity, but they shared a concern that low newsroom pay and rising wages elsewhere will make it harder to attract good people. ”I heard about a burger place [whose] fry cooks will make double what my reporters make,” said one. “We’ve got to start paying people or they’re not going to come into this field,” said another. Independent consultant and Kneeland faculty member Kevin Benz agreed. “I’ll go on the record saying it: corporate television executives must look at this. It is a moral issue, as much as it’s a business issue.”

After the session, Joan Barrett told me about a different but related concern: during the pandemic, young people — and especially those from underrepresented communities — lost the opportunity to learn about the business through internships and job-shadowing. So she and her team are putting on a virtual job fair next week called “Discover Your Pathway to a Career in Local Television.” WCNC staff produced explanatory videos and will lead live sessions describing various jobs at the station — everything from reporting and photography and the assignment desk and meteorology to marketing and sales. The eight free sessions are aimed at high school and college students, and slots are still available. (You can learn more and find out how to enroll here.)

All the news leaders agreed that remote interviews are here to stay, at least as an added tool if not the exclusive one. But the trickier issue is the evolving nature of news coverage. Stations did a terrific job serving up vital information to their viewers and users during the pandemic, often instead of the usual “breaking news” fare.

J Bates said that the emphasis on substance over sensationalism was already a priority for Scripps. “[Our] content strategy did more for morale than probably anything,” he said. “If it bleeds, it leads — gone. Live for live’s sake — gone. Breaking news for breaking news’s sake — gone. All of that has been fantastic for us. Now for the viewers? [The ratings] didn’t go down. I’ll give it that: they didn’t go down.” (The Atlantic just published an interesting piece by Amanda Ripley that digs into the story behind Scripps’s change in approach.)

“In our editorial decisions, we’re not just telling people what happened or what is happening anymore,” agreed Amy Beveridge, news director at Hearst’s WMTW in Portland, Maine. “It’s much more of the in-depth, explanatory stuff than it is the spot news, the things that just don’t affect as many people. I think that’s the big difference.”

But Beveridge admits it’s easy to slip into old habits if you’re not careful. “I think that there are times where we do fall into that,” she said. “People will pitch [a routine spot story] and I’ll be like, ‘If it’s something like that, it can be a VO/SOT.’ Our reporters need to be doing stories that have a beginning, middle and end, that have a protagonist, that explain something. That’s something that we need to remind people of daily.”

I came away from the Kneeland session with even deeper appreciation for the high stakes involved as people return to the newsroom. As Joanne Lipman wrote in that TIME story I mentioned earlier, “We have an unprecedented opportunity right now to reinvent, to create workplace culture almost from scratch.” And she adds: “Companies that don’t reinvent may well pay the price, losing top talent to businesses that do.”

Editor’s Note: As your newsroom confronts the new challenges of work after COVID, we’d like to hear about what you’re learning and what you’re doing differently. You can find us at cronkitenewslab@asu.edu.

Get the Lab Report: The most important stories delivered to your inbox