The transition to new leadership at Chronicle, the nation’s longest-running locally produced news magazine, is almost laughably amicable, especially by TV standards. But it raises relevant questions for any station wrestling with how to re-tool its legacy broadcasts for a new generation of viewers and wondering whether to invest in original long-form programming for an on-demand world.

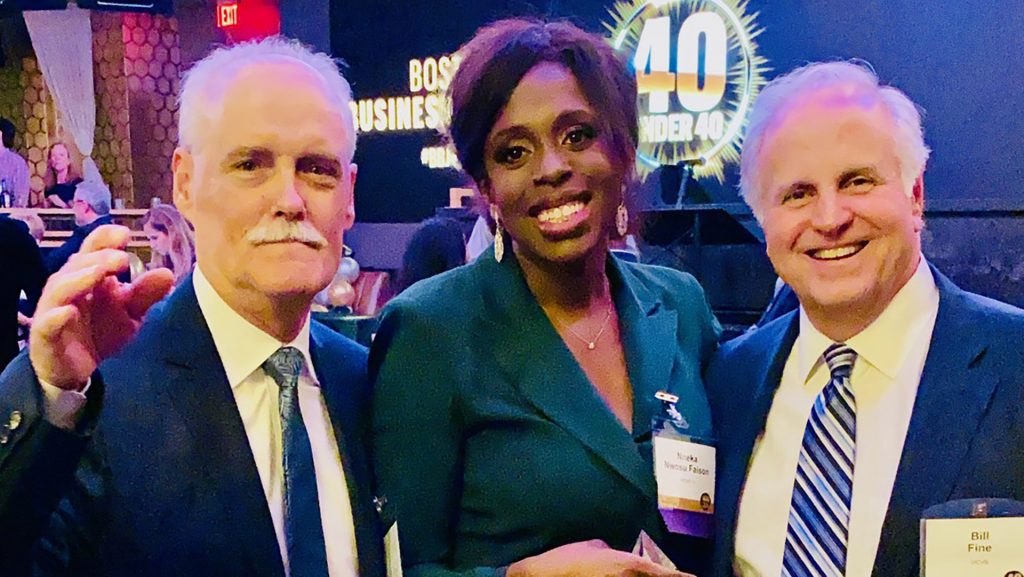

Nneka Nwosu Faison was born in 1982 — the same year Hearst powerhouse WCVB-TV in Boston launched Chronicle, now a revered New England institution. “I’m hearing from people who said they watched with their parents, and now they’re watching with their kids,” says executive producer Chris Stirling, who’s been with Chronicle for 35 years and has run it for the last 30.

At the end of the year, Stirling will hand off the 37-year-old program to a new executive producer, the 37-year-old Faison. She came to the program six years ago as a producer/reporter and was promoted to managing editor last January as a potential stepping stone to this new assignment.

I went to the station just outside of Boston for a chat with Faison, Stirling, and their boss, veteran general manager Bill Fine. “Chronicle has the luxury of being what it wants to be on any given night,” says Fine. The program has gone through multiple talent changes as it evolved, but it settled quickly on a winning format: a single-topic magazine every night at 7:30 p.m. “We’re looking more at the positive side of life for the most part,” says Stirling, who then quotes the station’s pitch: “Chronicle helps you make the most of your leisure time.”

That translates to a lot of lifestyle and travel stories, including a popular franchise that’s almost as old as the program itself, Main Streets & Back Roads, which explores towns all over New England. The first time the station commissioned market research, says Fine, “what we found was: ‘I know the news already. I want Chronicle to be something very different. Chronicle is dessert. I had dinner already. I want dessert.’ And Chronicle was that treat.”

But Chronicle also explores serious issues, offering the depth and perspective that a single-topic half-hour allows. “We do provide context in a time when people are suspicious of the news and information that they’re getting,” Faison says. “And we go find the stories that other folks don’t have the time to find. Even though it might on the surface look like a travel show, it’s much more than that.” The night I visited, the program was about millennials and money — the challenge of making ends meet while wrestling with college debt, aging parents, and of course kids of their own.

The daily broadcast competes effectively against syndication powerhouses like Jeopardy! (on CBS-owned WBZ-TV) and is highly profitable, says Fine. “People think of all news departments as somewhat similar,” he says. “Chronicle is differentiated. And we feel it actually differentiates the station as well: that one half-hour each night.”

So is the long-form news magazine show an idea whose time has come — again? Chronicle sounds like a pretty good model, especially in today’s world of expanding over-the-top services and the difficulty of standing out amidst a welter of choices. So why haven’t more stations tried it? Even Hearst produces only one other daily version, at WMUR-TV in New Hampshire.

“It’s not a bad idea, but it’s a very hard thing to accomplish now,” says Fine. “Chronicle is countervailing to the actual trends in the industry, because it’s easier to take the same number of people and just add another half hour of news relatively efficiently and cheaply. To really do it the way we do it, you would have to staff up.” Chronicle has its own staff of 22, including eight producers, two anchors, a reporter, and a producer-reporter. One of the anchors and the reporter also have regular newsroom assignments, and the program sometimes draws on other news talent.

“Part of the reason we’re still here and thriving is that 37-year history,” says Stirling. “If you started from scratch, and you’re competing with Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, all these things that didn’t exist, people don’t have the bandwidth to take in something new. And you’re a local entity trying to compete for eyeballs. I can see why people will be risk averse to that.”

Speaking of risk, all three executives are mindful not to make too many changes too quickly. Chronicle was a pioneer in high definition, adopting the format in 2006, when most people didn’t even have HD sets yet. “We want to avoid the reaction we got when we went all the way to HD and started letter-boxing some shows at the beginning,” Stirling recalls. “And someone wrote in and said, ‘Thanks for giving me another reason to die.’”

“We have to make sure we don’t alienate the audience we already have,” warns Fine. “It’s bringing them along as you introduce [younger] people too, and that is so much easier said than done. To be too young is a mistake for a legacy business. But to get younger is absolutely where you should be headed.”

Cue Nneka Faison. “Maybe it makes sense to have a 37-year-old taking over a 37-year-old show because I grew up in a household that watched local news religiously,” says Faison. “I remember having that habit of rushing home to watch television. But I also remember starting out as a reporter and having the phone in my hand all the time, in addition to carrying the camera and shooting all my stories.”

Faison has already built on Chronicle’s modest digital profile — basically a Twitter feed, an undernourished Facebook page, and clips on YouTube — with a fledgling podcast and a revived newsletter. She hopes to get the show’s anchors and reporters more engaged on social-media platforms. But mostly, we should expect subtle changes in story selection and execution. “We’re all news people. But we do understand that the audience enjoys the lifestyle part of Chronicle. And if we do lifestyle pieces, I would like to do them in a way that reflects the lifestyle of the demo that we’re trying to reach.”

Faison is only a year younger than Stirling was when he took over the show at 38. “It was a baby boomer driven kind of show,” he says. “And it reflected what that generation was going through. So now as we change to a staff that’s more in the demo that we’re after, I think it should organically reflect what those people are interested in.”

So the definition of victory sounds simple: reach more millennial viewers without turning off the loyal boomers. It will be Faison’s job to figure out how, both on the program itself and in its digital extensions. “I just hope that we are covering the same topics in a fresher way,” she says. “[Millennials] don’t have the same habits that our parents had, So I hope that a few years from now we are everywhere they are — and they are here. I want people to watch Chronicle a few years from now and think that it looks the same, but different. Does that make sense? It’s like what I told my makeup artists the day I got married: you want to look the same, but different.”