AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is the first of two articles on the newsroom recruitment crisis, which I believe represents a critical danger for the quality and ultimately the viability of local TV news. This week, I’ll look at why it’s increasingly hard for newsrooms to attract and keep promising new candidates. Next week, I’ll examine some steps stations and groups are taking or should consider to fix the problem.

What’s the biggest threat to the future of local TV newsrooms? The long-term challenge may be how to build a sustainable model around a new generation of consumers who will never watch a linear newscast at 5, 6, or 11. But news directors and their bosses are increasingly concerned about a more immediate problem: the pipeline of talent for both sides of the camera is drying up.

Ty Carver, who ran recruiting at Raycom Media and now has his own firm, recently published a long, impassioned screed titled “Extinction Alert?” — at least there’s a question mark — that sounds the alarm and calls for news leaders to respond on multiple fronts. “The television station stress level must be released…and soon,” he writes. “At all levels. Because trust me, some newsrooms are at a breaking point.”

“If there is one overwhelming challenge that I hear from every news director I talk to, it is that they’re not getting the same quantity of applicants for jobs that are open as we did maybe as little as three or four years ago. And they’re certainly not getting the same quality applicants that they were getting before,” says newsroom coach Kevin Benz. “It is truly the biggest pain point that I am hearing from news directors across the country.”

Lesley Van Ness, head of recruitment at Gray Television, has 200 MMJ (multimedia journalist) openings across the company. “So in 102 markets, basically every station is averaging two MMJ positions that are open, and those are the people generating that content every day for our audience,” she says. “It is our smaller markets that are really struggling, because they have a staff of 25 or less. So when you’re down two MMJs, it’s hypercritical that we fill those.”

“I’m actively seeking out news anchor candidates for five of our six stations,” says Michael Hammond, who recruits for Hubbard Broadcasting. “You might have trouble finding a producer, but news anchor is the top role you want to be in for most people in journalism. And the fact that we’re just not getting natural applicants is really unusual.”

What happened? The industry experts with whom I spoke are in remarkable agreement on what’s gone wrong. Here are the key factors they talk about.

Pay

Bob Papper of Syracuse’s Newhouse School has been studying broadcast newsroom salaries for decades and is the nation’s leading expert on the subject; you’ve no doubt pored over his annual salary survey for RTDNA. As far back as 1999, Papper compared TV news employment to “indentured servitude,” and he hasn’t changed his mind since. “The origin of the problem goes way back,” Papper told me. “What there’s been is no solution to it. For 10-15 years or more, this industry has grossly underpaid people compared to other options. And I would argue that the notion that this industry is going to attract the best and the brightest probably hasn’t been true for a long time.”

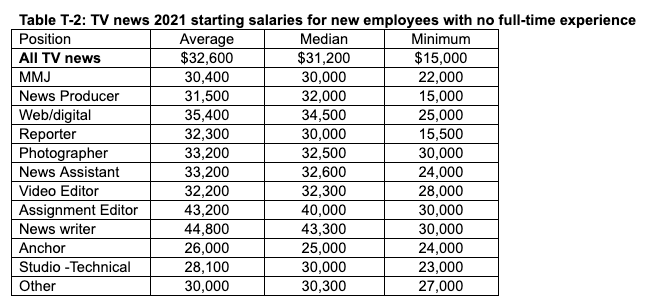

Check out this chart from Papper’s 2021 analysis and picture what it’s like to live on these starting salaries today — unless you already know.

“If you want to be a reporter, there are dues to be paid,” Papper says. “We exact a hell of a price, because we’re going to pay them maybe $30,000 a year to do that. Whereas they could take that skill set somewhere else for 45 to $60,000. And if you’re walking out of school with no debt, and you’re really determined, you can afford to do that. But if you’re walking out of school with debt, which is what most of these kids have, that’s an awful tough choice.”

To make matters worse, young people just starting out can make more money in supposedly menial jobs — one recruiter who didn’t want to be named mentioned flipping burgers at California’s In-N-Out chain — than taking an entry-level job in a local newsroom. My local supermarket is offering starting wages of $17/hour — $35,360 a year if you work 40 hours a week.

“I cannot tell you how often I am hearing from news directors who know that working at a restaurant, or at a fast food place, or doing some manufacturing job, those jobs are paying extraordinarily more money. We’re talking about 30 to 40% more,” says Benz. “You can go work at Target, or you can go work at Starbucks and get paid more, and they’ll pay you to go to college,” says Van Ness. “Entry level MMJs and producers are really doing a lot of the heavy lifting in those newsrooms on a daily basis,” she adds. “So then if they feel underpaid, they feel undervalued. They don’t want to stay.”

New options

Related fields are also a direct threat. “You can struggle for $30,000 and have three roommates and maybe get food stamps, or you can earn a good living almost anywhere in the country, working in corporate communications,” Papper says. Graduates of journalism programs are finding compelling alternatives to the newsroom, not just in PR and marketing but at companies increasingly interested in creating original content.

“Look, the education you get as a journalist is pretty significant,” says Benz. “And especially now that it involves digital skills and production skills and storytelling skills, those are very much in demand by everybody. Every major company in the country now has full blown media departments. They’re doing media and communications, they’re doing content marketing, they’re developing video and audio and podcasts. If you’ve got the skills, you’ve got lots of choices, and you don’t have to go out and have people yell at you and spit at you and tell you you’re fake.”

It’s not easy to admit, but local TV news just doesn’t have the cachet it once did. “I think that local television for years just had the mentality that, ‘Hey, we’re local television: build it, and they will come,’ kind of like the Field of Dreams movie,” Carver told me. “And we’ll offer a salary and somebody will take it. And for years, they put a job posting out and they would receive many, many, many resumés and have their pick of the litter. Today, that’s not the case.” Hubbard’s Hammond agrees: “I would say that television is no longer the bright and shiny object.”

The Bigfoot Factor

Because of the worsening talent shortage, larger stations are reaching lower down the food chain, snagging less experienced candidates who would once have been happy to find work in smaller-market newsrooms. That sets off a cascading set of consequences that is putting an even tighter squeeze on markets below the top 100. “And so this domino effect happens,” says Benz. “And when you get to the smallest markets — around 120 plus, 150 plus — there’s nothing left.”

“A good producer goes to a top 50 [market],” Van Ness says. “So how is someone in market 150 ever going to get that standout entry level grad from ASU, or from Mizzou, or from Syracuse? They don’t even look at our smaller markets. If you could go to Phoenix, you’re going to go to Phoenix over Sioux City, Iowa — no disrespect to Sioux City, Iowa.”

Hubbard’s Minnesota-based Michael Hammond used to recruit heavily from colleges like nearby St. Cloud State University, but now he’s losing graduates to larger out-of-state cities like Des Moines and Madison. As for candidates of color, who are in particularly high demand, “When I reach out to these students at virtual career fairs, if I can get them to even speak to me, [they already] have job offers from the national news outlets: Fox, CNN, MSNBC, NBC national in New York. So how am I going to recruit these students to go to Rochester or Duluth, Minnesota, when they have a job offer in New York?”

Ironically, while interest from big-city newsrooms may sound like a great opportunity for young graduates, the experts say that moving too soon to a large market can backfire. Markets like New York and Los Angeles are “not getting the quality and experienced candidates that they used to,” says Benz. “And so what’s happening is they’re picking candidates from markets who probably needed one more step.”

“It is incredible to me, honestly, how many bigger markets I’ve seen hire MMJs who aren’t ready,” says Van Ness. “And my fear is, when you put someone in a market they are not ready for, and they’re thrown to the wolves, no one’s gonna hold your hand, and you are just constantly criticized. At some point, you give up, and you quit, and you leave the business — and we lose good journalists.”

Quality of life

It’s no secret that the pandemic has triggered a massive re-evaluation of the nature of work across all industries, with many workers taking a hard look at the impact of their jobs on their other priorities. So many have quit that it’s being called “the great resignation.” But working in a local TV newsroom has always made excessive demands on your personal life.

Gray recruitment honcho Van Ness worked her way up from MMJ to anchor at Quincy Broadcasting but stepped away from the newsroom after nine years at the anchor desk so as to have more regular hours with her two young children, ages two and nine months at the time. Now she deals with the changing expectations of a new generation of candidates. “You have to make a lot of sacrifices,” she says. “You’re sacrificing hours working weekends, working holidays. I don’t know what the answer to that is, especially now in a world where news is 24/7. There is this constant platform that we have to create content for that is just never-ending. And I think that even creates more stress and pressure on people.”

“It’s leading to stress, burnout, mental distress, mental health concerns,” says Ty Carver, whose post begins with the story of a highly qualified executive producer in tears and on the verge of leaving the business altogether. Post pandemic, more candidates want to live closer to home or family or in cities where they feel comfortable. Gone are the days when up-and-coming reporters and producers would routinely move anywhere in the country every few years, working their way up the ladder. “They’re choosing to live where they want to live,” Carver says. “Next to family, friends, the restaurants they’re used to, the culture they’re used to, etcetera, versus playing that kind of the chess game that many in the industry were used to for decades.”

The “Snowball Effect”

These factors build on one another and exacerbate an already critical challenge for newsroom leaders, who are experiencing “stress and burnout” themselves, Carver says. “It’s a snowball effect. They’re already doing more with less people, and now they have empty seats. And they had turnover as part of this ‘great resignation.’ And it’s a self-perpetuating situation that is just rolling downhill and gaining momentum. And how do you fix it? Because it’s not righting itself.”

Next week, I’ll take a crack at answering that question. Our experts had plenty to say about the problem; we’ll see what they propose as solutions, and I’ll add a few suggestions of my own.

Get the Lab Report: The most important stories delivered to your inbox