As a rule, a text from your boss at 11:30 on a Friday night does not portend good news. But the message Sinclair’s CEO, David Smith, sent to his news chief Scott Livingston four years ago became the seed of a project that is still going strong — and represents an extraordinary and successful commitment to single-topic investigative reporting.

Smith (now Sinclair’s executive chairman) had just seen the movie Spotlight, about the Boston Globe investigative team that exposed years of sexual abuse and cover-up by Catholic priests and their leaders. “He left the movie theater,” says investigative reporter Chris Papst. “He called our senior vice president of news. And he said, ‘Who’s our Spotlight team?’ And Scott said ‘We don’t have one.’ ‘Well, we need one.’ So that’s us. That’s how it got started.” Life imitating art imitating life.

Livingston caught the first matinee the next morning — “It was well worth my time” — and then pulled his colleague Bill Anderson and a team together that Monday to brainstorm. “With four thousand people in news, why aren’t we doing this kind of journalism?” Livingston asked. “We need to figure out how we can have this kind of impact.”

The result: “Project Baltimore” — a plan for Sinclair’s Baltimore flagship WBFF-TV (branded as Fox45) to establish a team focusing only on education, a perennial problem in the city’s well-funded but badly underperforming public schools.

The Project Baltimore group works in a separate building, isolated from the newsroom, free of daily news obligations to “feed the beast,” in Livingston’s words. “For this to be successful, it’s critical that we stay on point,” he says. In exchange, the team is expected to deliver consistent enterprise reporting — at an ambitious pace of two original stories every week. “It’s like a journalist’s dream to be told you can focus on one thing for the foreseeable future,” says the project’s executive producer, Carolyn “Carrie” Peirce. “Just focus on this, do it well, and don’t get pulled off into other things. I mean, what journalist wouldn’t love that?”

Reporter Papst, two photojournalist-editors, and an investigative producer round out the five-person team, which hasn’t missed a beat on its beat since starting in March of 2017. “We’ve now been doing it for three years, and we have moved on systematically from topic to topic to topic,” says Papst. “And as we continue to do more, I think our stories are only getting better, because we’re building a better reputation and a better brand in the market. And more people are coming to us knowing that this is what we do.” “My concern was whether this topic affected enough people and whether or not people would care,” says Peirce. “And it’s only proven to be more impactful than I ever thought it could be.”

The project has expanded to the whole county and other nearby districts, focusing on the often-underrepresented voices of students, parents, and taxpayers, and on holding public officials accountable. “Every single story we do has another layer to it,” says Peirce. “And a lot of them are stories about people that have been trying to go up against a massive education system, and they’re just being shut down and they need help. And until this unit was created, they weren’t getting anywhere.” “They’re lost. They’re swallowed up in the system,” Papst adds. “There have been numerous instances where people have called us and have gotten what they’ve wanted, when they have tried for years to do it, and they can’t do it on their own.”

Two hallmarks of Project Baltimore are consistency and tenacity. The two weekly stories always air in the second block of the 10 p.m. news on Monday and Wednesday and are repeated the next morning. And rather than the run-and-gun pattern typical of so much news coverage, the team sticks with a story as it develops, no matter how long that takes.

Watch one of the team’s highest-profile stories, involving a sex offender enrolled as a student.

After the team discovered a 21-year-old registered sex offender who had been enrolled in a Baltimore County high school with the principal’s permission since age 19, it ended up producing more than two dozen stories on the subject, unearthing new victims and charges of abuse. “We do the story, and then 20 people reach out to us. We do a few more stories and 40 more people reach out to us,” says Papst. “And it snowballs and snowballs and gets bigger and bigger. And when this is all over, the state’s attorney’s office has a new policy, the school board is drafting a new policy, the state is passing laws.” And the offender is now in jail awaiting trial on the latest charges.

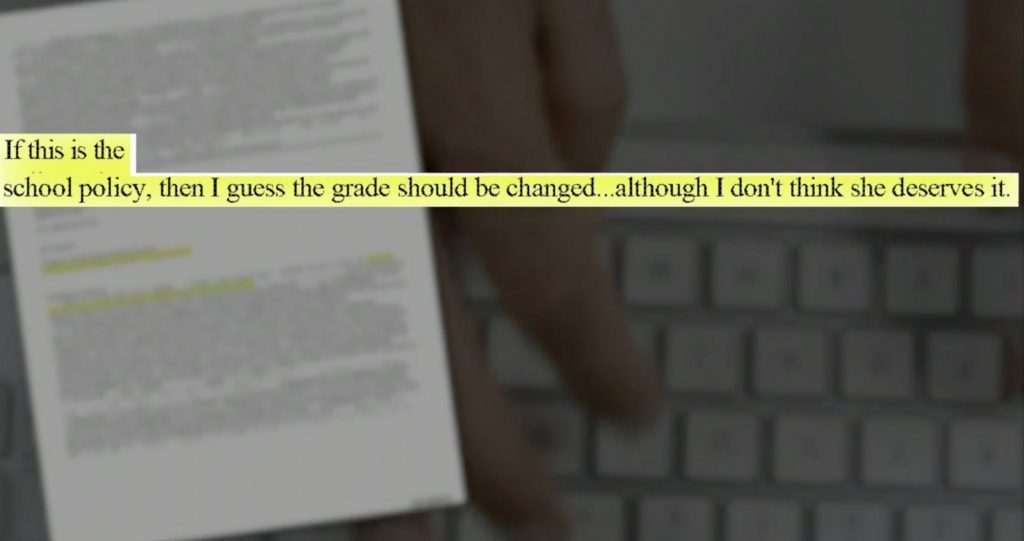

The most dramatic example of sticking with the story: a grade-changing scandal that the team is still reporting on, more than three years after checking out one teacher’s tip that failing students were being pushed through the system with artificially inflated grades. More leads poured in, and when the city stonewalled its internal investigations into the widespread problem, WBFF sued to obtain key documents — an expensive battle that finally produced a court victory and (much later) a trove of relevant emails.

In addition to examples of failing grades adjusted upward, the emails told of students passing without showing up to class and teachers under pressure to change grades and starting to push back. “We received more than 8,000 emails from that lawsuit related to grade-changing,” says Peirce. “And we divided them up, and we read all of them.” Adds Papst: “It was really eye-hurting.”

Project Baltimore is planning a February documentary on the entire grade-changing investigation, which has resulted in major policy changes by the city school board. The team produced another documentary on the high school sex offender that aired in June. Until the coronavirus pandemic struck, the team was also producing monthly “Project Baltimore In Depth” reports that took up all but seven minutes of the newscast.

Even the pandemic hasn’t broken the project’s weekly rhythm — partly because the virus has had such a profound impact on education. The WBFF newsroom takes care of the school-related day turns, but the Project Baltimore team began producing one enterprise story a week on COVID-19 and education while devoting its other slot to existing investigative story lines. “We realized that we needed to find a way to cover this unprecedented situation and add to the story, but with our unique expertise and skills,” says Peirce.

Project Baltimore has won multiple awards, including back-to-back honors from Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE). The ratings actually improve when the team’s reports air, in defiance of conventional TV wisdom that education stories don’t “sell.” Chris Papst, somewhat skeptical himself at first, became a believer a couple of months in when one of the station’s anchors thanked him for explaining how schools are funded. “People really don’t know how this stuff works,” he says. “They’re just fed the same lines over and over again. So I was more willing to take a risk on a TV story that may not be sexy, that educates people. And I think that’s been a big plus for us moving forward: that we will do those stories when other people would rather cover, you know, a cat in a tree.”

Scott Livingston agrees that the project’s editorial distinctiveness helps drive its success. “If they turn to you, it’s because you’re offering stories they can’t see anywhere else,” he says. “We’ve created must-see TV based on great journalism.”

Sinclair now has 25 single-topic reporting initiatives in 23 markets — Baltimore and Seattle have two each — but none of the other teams is fully “quarantined” like Project Baltimore, an original hot-house experiment that blossomed in its own soil and provided the seeds of innovation for the rest of the group.

“It’s fairly easy to share the ‘what,’” says Livingston. “We’re really pushing all of our newsrooms on the significance of sharing the ‘so what.’ If we focus on impactful reporting and quality journalism, people will watch. That’s what’s so exciting about our future.”