Words matter. Journalists, of all people, appreciate the power of the reporter’s pen and voice. Yet in newsrooms across the country, we continue to use language that squashes innovation and holds us back from transforming our newsrooms at the pace needed to match the digital disruption around us.

So here’s a New Year’s wish and a challenge to news leaders and storytellers: five culture-killing phrases to stop saying, or at least actively challenge, in the new year.

This response to ideas sends the message that there are rules, and those rules are not to be questioned but are simply to be obeyed. Or, as a colleague concisely put it to me recently, the takeaway is: “Be quiet. Your ideas don’t matter.”

If our audiences were growing, news revenues were robust and sustainable, and trust in media was high, I’d be more sympathetic to simply following the old rules. But none of that is true. The core principles of journalism (like accuracy and fairness) do endure; but we should be relentless in re-examining our practices — how we do what we do.

After decades working in local TV newsrooms, I now get to see this issue from the other side. Here at the ASU Cronkite School and at other fine journalism schools across the country, we are graduating a cohort of mission-driven, motivated, multiskilled journalists. Bonus: They happen to be mobile-first digital natives, members of the next generation of information consumers. Who better to help us reimagine and reinvent our local newsrooms? Forcing them into our ‘system’ without actively soliciting their input is a huge missed opportunity.

I often advise graduating student journalists to “learn the rules, then break them” at the newsrooms they join; the same advice applies in reverse to newsroom managers: Invite and welcome questions and challenges to “how we do things here.” A manager can always decide to keep specific legacy practices, but we can only benefit from fresh eyes and thoughtful review.

This dismissal contains a thinking error common in legacy newsrooms: We’ve historically relied either on our ‘gut’ or (unreliable) overnight ratings to make snap judgments, and we lack the discipline found in digital media companies around metrics, measurement, and post-mortem review. (After a tour of Silicon Valley platform companies, I shared seven lessons relevant to newsrooms.)

When I hear “we tried that before, and it didn’t work,” a few things cross my mind. The first is that it immediately shuts down the person who made the suggestion, and sends that same message to anyone who witnessed the exchange. This can’t possibly be in the best long-term interests of fostering a newsroom culture of innovation.

The second thing I wonder when I hear “we tried that before and it didn’t work” is: How do you know? Often, the answer turns out to be based on either weak data (“It didn’t do well in the ratings”) or just personal opinion (“It wasn’t good TV”). Each has flaws that merit at least further experiments. Nielsen ratings are themselves highly variable and unreliable; sample sizes are smaller than ever, amplifying errors; and unmeasured factors can commingle to blur actionable conclusions: What aired on other channels? Was the weather good or bad for TV viewing?

Legacy newsrooms would benefit by adopting the rigor around intentional experimentation commonly used at platform and technology companies:

- Define the experiment in advance (what are we trying to test?)

- Define success metrics in advance (how will we know success?)

- Measure the results and hold a post-mortem review afterwards, to compare the hypothesis to the results (what did we learn, and how should we adjust?)

As the adage goes, the only true failure is the failure to learn (If we knew how to evolve our legacy news practices for the digital age, we’d just do it.) So a culture that encourages purposeful experimentation, with rigor around measurement and lessons learned, means that we are never done when it comes to trying things.

In Buddhism, there is a concept called “beginner’s mind.” It’s about being open to possibilities and not being fixed in ways of seeing. Legacy newsrooms could prosper by adopting this beginner’s mind.

This well-intended question has been problematic for some time. Historically, it was asked in an editorial meeting filled with a non-diverse group of decision-makers who did not reflect the community they were charged to serve (alert: this is still true in too many newsrooms).

Understanding those limitations, many newsrooms have worked to incorporate more data into their editorial process. Today, the way we answer “What’s everyone talking about?” is often via what’s trending on social, as indicated by social listening tools like CrowdTangle or by Twitter’s trending list.

.

News leaders need to understand that this ‘answer’ has its own, potentially severe limitations. The short list would include: What’s trending isn’t the same as what’s important; a very small percent of the audience drives most social activity, so ‘trending’ doesn’t truly represent the audience; and it’s been well documented that bad actors can manipulate social discourse in ways that create trends that aren’t real. Perhaps worst of all, a focus on what’s trending distracts too many local newsrooms to chase engagement metrics, rather than direct engaging with their community.

In 2020, journalists can ask smarter questions than “What’s everyone talking about?” Here are a few:

- What does our community need to know more about?

- What issue or problem could we help explain and add context to?

- What are the important false narratives on social that we could fact-check and correct?

- What stories are being underreported due to trending ‘noise’?

- And yes, we should continue to strive to understand what are the conversations happening in our community, with or without us. So we might ask: How could we as journalists add value to what people in our community are talking about?

There’s also a lesson here about diversity of voices. Diversity today isn’t just a responsibility, it’s a smart audience strategy. We need diverse voices in our newsrooms to better serve the diverse needs and interests of our communities. It’s necessary but not sufficient to have those voices ‘in the room.’ Those voices also need to be heard, and need to be empowered to make key editorial decisions.

This statement contains the now-questionable assumption that there are ‘TV people’ who are somehow different people than web users. Sure, maybe that argument worked 15 years ago when TV remained the dominant source for news and the internet was still an upstart. Today’s audiences move from screen to screen. In fact, they are far more integrated in their use of screens than the legacy broadcasters who seek to serve them, and they follow what interests them from one device to another.

Research by SmithGeiger has tracked screen use by time of day and captured the fluid and seamless ways audiences are flowing between platforms. According to Seth Geiger, the ubiquity of mobile is driving this phenomenon, with active usage of mobile and live linear TV in the morning, to apps and the web during the day, back to mobile and a mix of streaming, mobile, and linear TV throughout the evening and into bedtime.

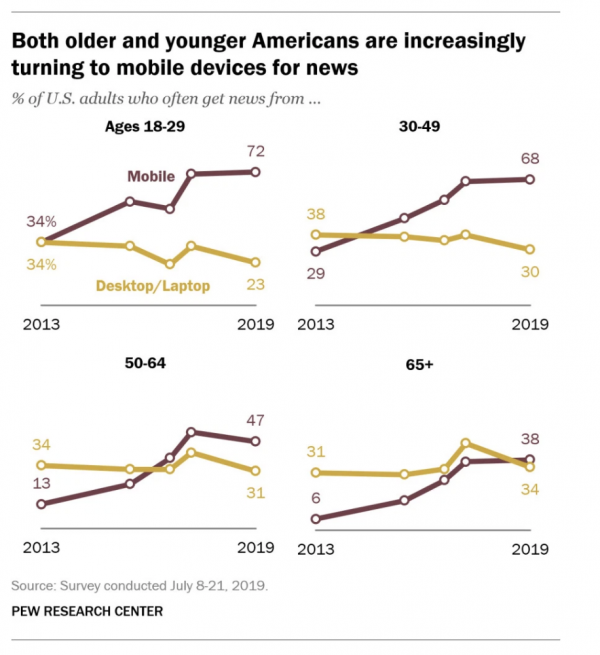

That’s true even for the oldest Americans. A study by Pew Research showed that, for the first time in 2019, Americans age 65 and older preferred mobile phones as their first digital screen for news.

It is now more accurate to say people are information consumers who move from screen to screen. TV does some things better (and some worse) than digital, and vice versa. Social media has its own strengths and weaknesses. Audio treatments of stories are becoming more relevant as podcasts and voice assistants gain in popularity.

Since our audiences access news in many ways, and each platform has particular strengths and constraints, a more productive way to lead a conversation might be: “How could we most effectively present this story for: the TV audience? the digital audience (and, mobile versus desktop)? the social audience? and, the audio audience (both on demand via podcast, and voice-activated)? These are harder but more relevant questions that can lead us to smarter, platform-specific storytelling.

There is perhaps no oft-spoken newsroom phrase that more clearly displays the disconnect between legacy news organizations and their audiences than the put-down “We already did that story.” Perhaps the only worse catch-phrase is its corollary: “The competition already did that story.”

The embedded harm is two-fold. First, this dismissal errs by treating stories as static objects, one and done. Good stories and important stories evolve and unfold; like an onion they can be peeled to reveal deeper layers; they can be advanced and explored. Second, this declaration projects an arrogance of reach that is no longer true, if it ever was. The (inaccurate) assumption contained in “we did that” is: “the audience saw it.” When the top-ranked newscast in a market gets, say, a 3.0 rating in Nielsen, by definition that means that 97% of households with TV’s in that viewing area did not see the station’s report. The throw-away of “we did that” presumes wrongly that message sent is the same as message received.

“The competition already did that” is an extension of this same flawed logic. Again, given the actual viewership numbers of a competing local TV station’s newscasts, we’d be better served by arguing that ‘Netflix already did that’, because today’s true competitors for our audience’s time and attention are more likely to be a streaming service or social platform than that TV station across the street.

On important stories and those that hold audience interest, we should ask better questions:

- How can we advance this story?

- What doesn’t the audience understand?

- What more could we find out?

- What other questions could we answer?

- What misconceptions could we correct?

- What other perspectives could we offer?

These are great questions for a news director to pose. Smart reporters will frame their follow-up story pitches through this lens.

There is a third level of sin in the “we did that” dig, one that perhaps exposes the most existential threat latent in legacy newsrooms. We have historically emphasized “recency over relevance,” as my Cronkite News Lab colleague Andrew Heyward puts it. Saying “We did that already” reveals our focus is on our daily newscast schedule as opposed to on our audience. In a way, “we did that” is an extension of meeting the daily newspaper deadline, the idea of “yesterday’s news.” Once the story is “published,” the internal newsroom experience for reporters is “I’m done with my story.” The impulse is to move on, to find the next story. Culturally, we even sometimes frown on reporters who pitch follow-ups to the story they did the day before, as though that’s lazy. We may even say: “Do you have any new story ideas?”

This is inside-out thinking. The focus is on our schedule, our work product. If we indeed work for the audience, we need to think outside-in. What does the audience need to know from us? In fact, the “end” of our day – broadcast or publication – is the beginning of the audience’s experience with the story. Listening to their responses and reactions, made easier by social media, creates the exciting possibility of true dialogue about the news. We can learn from our audience as they respond to our reporting, to find follow-ups, fresh angles and sources, and new questions to answer.

If we are truly to put our audience first, rather than our own daily production workflow, we will embrace the update, the story advance, the iteration and the elaboration because good stories are more like journeys than destinations.

Language matters. News leaders set the tone with the language they use, and can crush or cultivate a spirit of innovation with just a few words. So here’s to zealously defending the core principles of journalism, while welcoming thoughtful examination of our practices and assumptions. Here’s to asking smarter questions, using rather being used by data, and truly putting the information needs of our audience first.

Got a phrase you’d like to see banished from newsrooms in 2020? Join the conversation by sharing it on Twitter and tagging @cronkitenewslab.

Working on my latest for @CronkiteNewsLab — on culture-killing language used in newsrooms. What’s an expression you’d most like to see banished? (I’ll start: “We did that story already.”)

— Frank Mungeam (@frankwords) January 8, 2020