Eyewitness News. The term has permeated local TV around the country and mutated into so many forms that it’s hard to remember it was once a unique concept that changed the business forever and holds profound lessons for today. But the man who invented the format remembers every detail.

Al Primo was a fledgling news director at KYW in Philadelphia in the mid-1960s when “the whole magic happened,” he says. Most of the newsroom employees, including behind-the-scenes editors and producers, were in the same union — AFTRA. Primo discovered that the union contract permitted him to put any of them on TV and, provided they were reading copy they had written themselves, not pay them a dime more. Eureka!

“I took the four [least telegenic] guys and made them producers,” Primo recalls. He then took the ten others, ascertained what their interests were, and turned them into beat reporters, covering City Hall, the arts, education, medicine, transportation, and more. They may not have been classic TV types, but Primo says “there’s beauty in everyone…they were ‘presentable.’” And within less than two weeks, “they’re coming back with stories that nobody else had” — Primo calls them “mini-scoops.” He peppered the program with on-scene reports and populated the studio with his new team of on-air reporters, overcoming the veteran anchors’ fears of being turned into mere “news jockeys.”

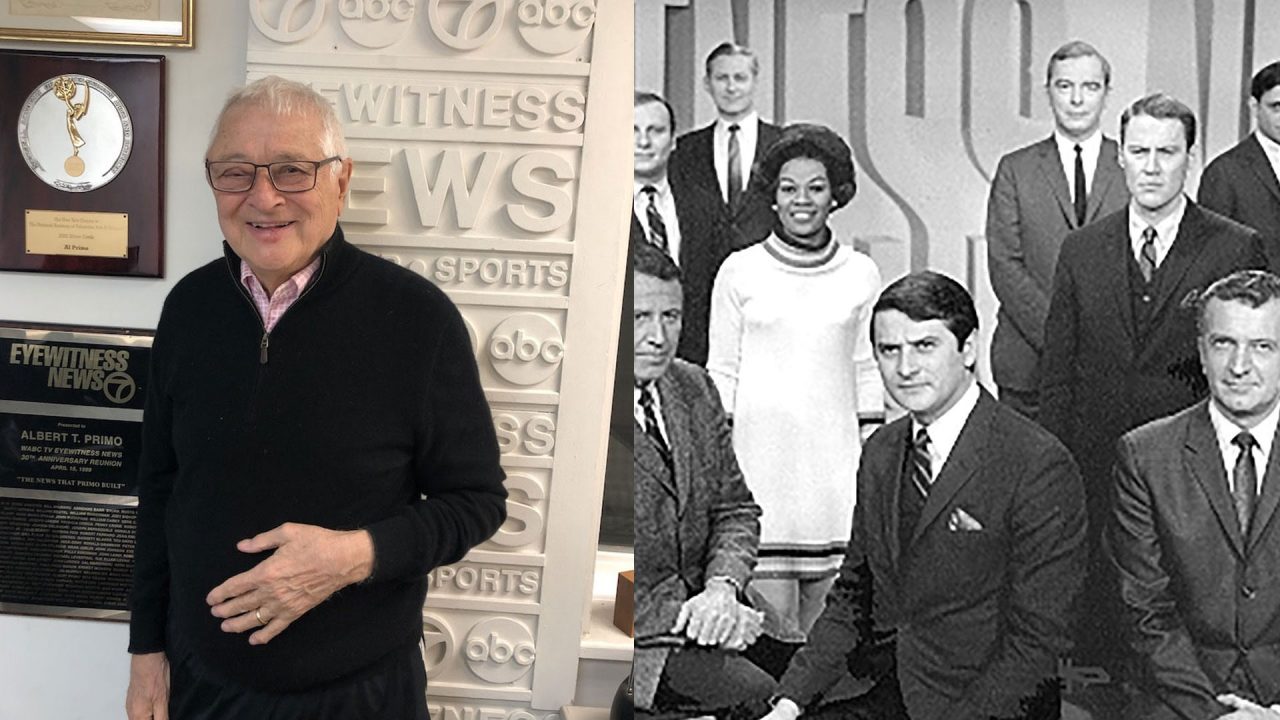

Primo didn’t invent the name “eyewitness news” — Westinghouse was already using it as a show title in Cleveland — but Primo believes the beat system he created in Philadelphia in 1965 was the first of its kind in local TV news. KYW went to #1, and Primo went to NY, to WABC, taking the name and the concept with him.

The station was so bad at the time that ABC network head Leonard Goldenson asked Primo: “Why would you want to come here?” But there was a budget to hire reporters and a “wide open” mandate to try something new.

As Primo walked to his office on Manhattan’s West Side every day, he shared the sidewalk with a diverse parade of idiosyncratic New York characters — a sharp contrast to the all-white, all-male newscasts of the day. Primo was determined to fill his team with people more like the people he wanted to reach. “God delivered this beautiful message to me. If you’re going to get ratings and you’re going to get people to watch you, you’ve got to have their kind on the show. You’ve got to find those people.”

Among the people Primo found:

- Melba Tolliver, a secretary at the company, became the first African-American woman to anchor a network newscast when on-air personnel went on strike and she was tapped to fill in for Marlene Sanders. Primo made her a reporter and launched a long and distinguished career.

- Milton Lewis was eking out a living as a tipster at City Hall when Primo tapped him to join the staff and assigned him the City Hall beat. His delivery was so odd that Primo gave him a catch phrase — “Now listen to this!” — so viewers would get the point of each story: it became his trademark.

- Jerry Rivers was an activist lawyer who felt so ready after Primo’s pitch that “trying to make absolutely certain that he didn’t break into the studio and put himself on the air was a challenge.” Primo convinced him to change his name back to Geraldo Rivera. You know the rest.

- Rose Ann Scamardella was working for the city — she had never reported a day in her life — when one of Primo’s colleagues suggested her to Primo as the “Italian lady” he wanted for the team. Scamardella became a star reporter and anchor who inspired the Gilda Radner character “Roseanne Roseannadanna” on Saturday Night Live.

Presiding over this motley cast and other equally colorful colleagues was the sandpaper-and-silk anchor team of Roger Grimsby and Bill Beutel. “Broadcast journalism is a team sport,” says Primo, and he branded his team relentlessly, down to the smallest details. Primo famously made everyone wear matching blazers emblazoned with the station’s logo, but he also pushed his street reporters to poke the Channel 7 mic logos into as many shots as possible, including the competition’s. “Localism and local news dominance was paramount in my mind from the beginning,” Primo says. “It was infused in everybody in that room…we can make it if we’re the New York station, we’re the New York people.”

It was a potent combination: seasoned anchors providing irreverent wit (Grimsby) and reassuring warmth (Beutel); a lot of laughter and what looked like natural rapport on the set; and bubbling through it all, the “eyewitness news team” — a crew of authentic local types who blended perfectly into the neighborhoods they covered with a relentless focus on the regular people who lived there. “People can tell their stories better than you and I can write them,” Primo is fond of saying.

Channel 7 Eyewitness News went on the air on November 17, 1968. It took 18 months, Primo says, but WABC went to #1 and remains a powerhouse today. Primo eventually became VP of News, adapting his formula to the other ABC-owned markets.

Primo is 83 now, and still working: he created a news show for teenagers, Teen Kids News, that’s syndicated to nearly 200 stations and made available without commercials to thousands of schools. We met in his unpretentious second-floor office on a commercial street in Old Greenwich, Connecticut.

Primo’s legacy? It’s complicated. The “eyewitness news” concept swept the business, but many people remember him for the more formulaic elements of local news as we know it today: the news team as a “family,” the relentless branding, and the often-mocked banter among the anchors. Wikipedia’s entry on “happy talk” credits Al Primo as its inventor.

But what of Primo’s pioneering insights about neighborhood-based journalism by a team of quirky, indigenous beat reporters who are as diverse as the people they cover and who still go after “mini-scoops” that no one else has? Somehow that got lost in translation. “There’s a sameness in broadcast journalism today that’s absolutely frightening,” Primo says. “That’s a big problem that has to be dealt with.”

So what’s his answer? Despite his place in the local TV news pantheon, Primo has no trace of pomposity and offers no easy solutions. “There’s no general formula or prescription for success.” That said, I was able to coax out some advice for today’s practitioners:

- Concentrate on distinctive reporting — “anything that’s innovative or original” — rather than stringing together routine video.

- Worry less about the mechanics of live production and more about the stories; try to have at least “one great piece” in every broadcast.

- Instill a sense of mission in your people so they’re not “getting it done by rote.”

- Pay attention to as many details as humanly possible.

- And perhaps most importantly, respect your viewers and reward them for the time they spend with you. “Let the audience know that you take it all pretty seriously, you’re having fun doing it, and it’s important work, and it’s socially redeeming time for them.”

Primo’s story is a testament to the power of truly local journalism, of building engagement and trust by hiring people who know their beats and their communities, who walk the streets where they live, and who talk (and listen!) to people about what matters most to them. 50 years later, that feels like a fresh idea.

Is your inner Primo dying to come out? Share your innovative ideas with us at cronkitenewslab@asu.edu. We’ll check them out.

Related:

AUDIO: Eyewitness News with Al Primo. Listen here.