If Jonathan Adkins, who oversees the broadcast news operation at Cleveland’s WKYC, wants to see the dramatic effects of COVID-19 on TV news production, all he has to do is go downstairs.

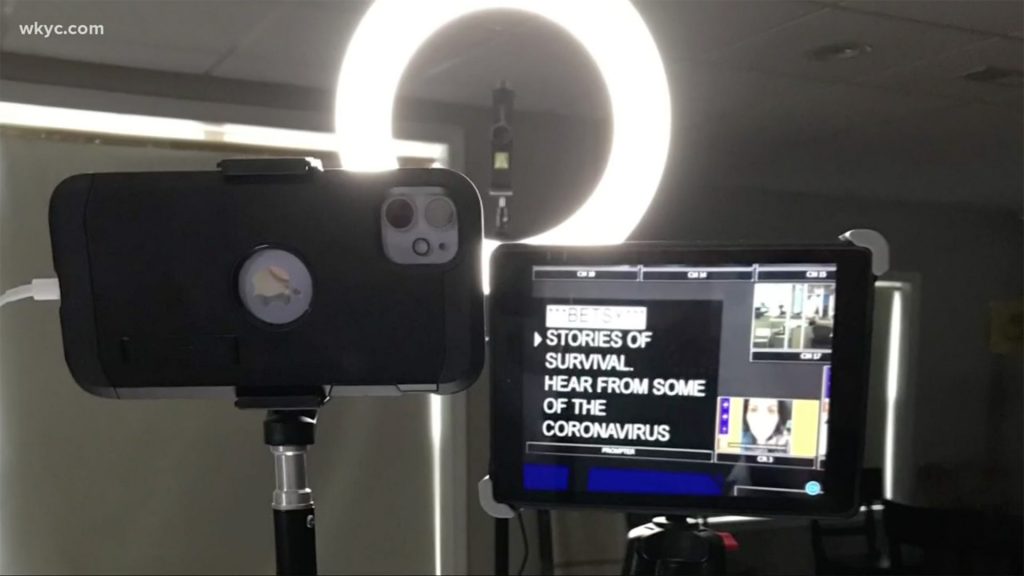

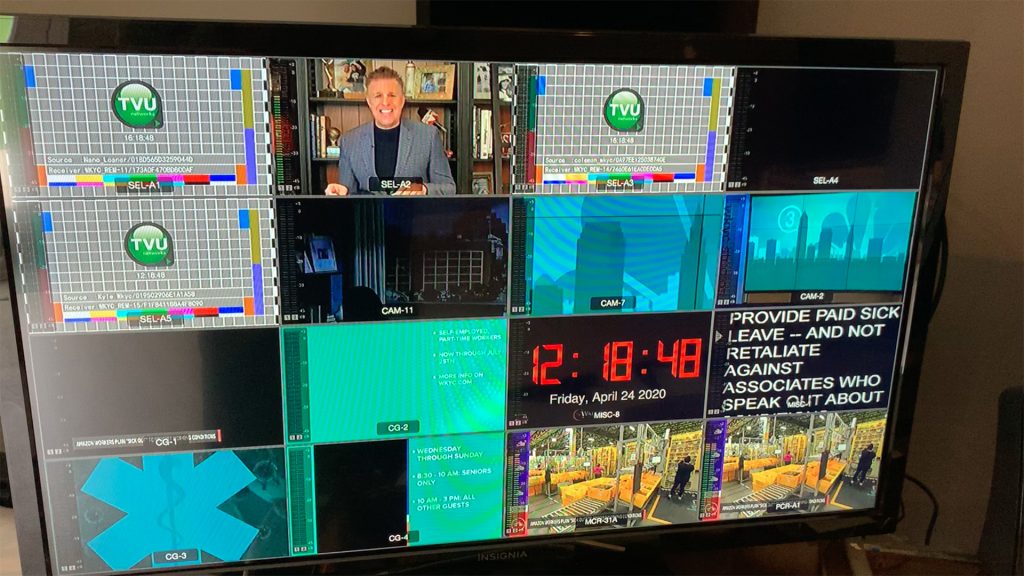

“If a year ago, you had told me I could sit in my basement in my house and see 16 live feeds from the field, have direct interaction with the talent on the set, and be able to watch feeds and our broadcasts with less than a half second delay, I would have thought you were crazy,” he says. Adkins can even re-set the teleprompter from home.

“An industry that has been famously plagued by tradition — we still put on broadcasts that look the same way they did when we were all children, and our parents were children — was suddenly forced to innovate,” says Adam Miller, Director of Content at WKYC. In that role, which station owner TEGNA has introduced around the country in lieu of a more conventional management structure, he oversees both Adkins and a head of digital, Denise Polverine.

“If we go back to the way things were, we failed,” Miller says. Adkins agrees: “I think our eyes have been opened over this last year to say, ‘Hey, it’s not acceptable to do things in the manner that we’ve done them before.’ We need to be different as an industry to be able to compete with those other industries that have been accepting [innovation] for a lot longer than we have.”

But what does that mean, exactly? I asked the three WKYC executives, along with veteran anchor Russ Mitchell, to share a conversation that’s going on in every newsroom in America — or at least should be: Which innovations prompted by the pandemic should survive it?

The most obvious legacy of coping with COVID is the ability to work and cover news remotely. The executives expect their staff to return to the newsroom when it’s safe, but that doesn’t mean returning to routines that they’re better off leaving behind.

Example: the dreaded morning meeting. “The days of going into a conference room for a morning editorial meeting with 30 people, and four people giving the ideas and the other 26 not really wanting to be there — those days are gone,” Adkins says. “We need to evolve.”

Reporters will come to the newsroom when it makes sense, but they can also go straight to their stories when that’s smarter and faster. And after a year of putting employees’ safety first, Miller and his team say they’ll take advantage of remote technology to be more flexible in accommodating personal needs. “There are so many different examples where this is going to benefit employees in terms of striking a better work-life balance,” Miller says. “Everything is on the table. We’re having these conversations now about what that flexibility may look like.”

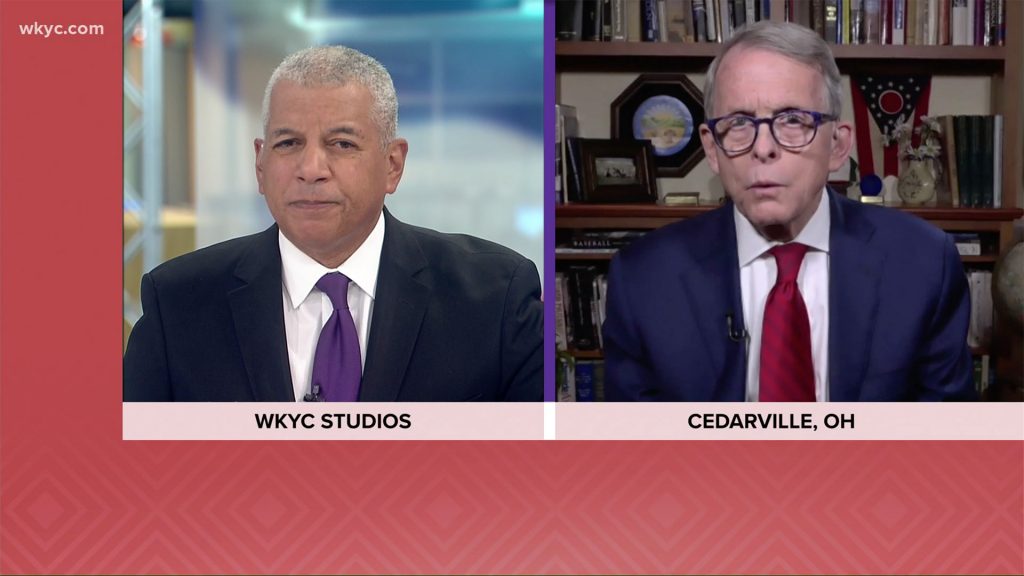

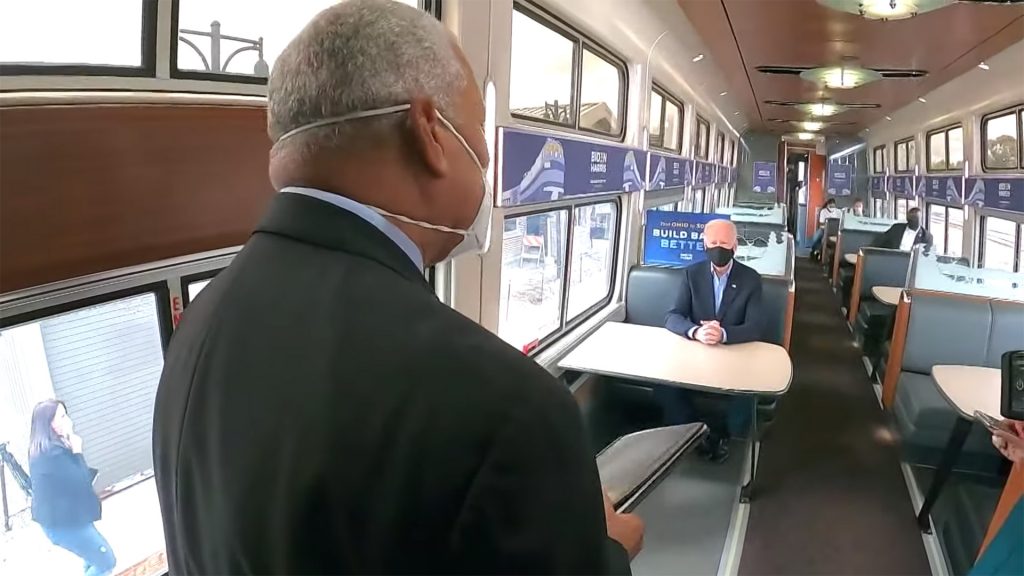

Newsgathering will change permanently too, largely because journalists and viewers alike have grown accustomed to interviews via Zoom. “It opened the world for us,” says Russ Mitchell. “If we want to interview a lawmaker in Columbus or Timbuktu, you just do it on Zoom. It’s incredibly easy.” “It suddenly feels like the news gods looked down upon us and said ‘Access granted,’” Miller says. “It’s this YouTube generation, where if your video suddenly is a little blue, or the audio suddenly choppy — look, we never strive for lesser quality, but the viewer is much more accepting. And I think that that combination of a more accepting audience, combined with the access granted, makes for a better content experience. The world is our oyster. That will not change, it should not change.”

Digital head Denise Polverine says that thanks to the pandemic, she no longer has to evangelize about the importance of creating original digital and social content. “As the digital director, I’m always trying to get reporters to think digital first, and producers to think digital first. I don’t have to make that case at all anymore,” she says. “We’re leaps and bounds ahead of where we were even just a year ago with getting everyone to engage on digital and social. So we’re much more strategic, we’re much more engaged as a group of reporters, no matter what your role is in the newsroom.”

Polverine says the sheer volume of vital COVID-related information — a “fire hose,” in her words — forced her team to be more efficient, using Slack as a substitute for in-person contact, with surprisingly good results. “When we were in the office, we felt very efficient,” she says. “But it wasn’t until we really were forced into this role and all working in different spots that all the tools came into play in a big way for digital. We’ve been able to pump out more stories, more accurate stories, cross-checking each other really quickly, just by using some of those simple tools, which we will continue whether we’re in or out of the office.”

Like so many other stations, WKYC expanded its original slate of digital content, with new series like Faces of COVID; pandemic-focused Q & A’s with medical correspondent Monica Robins; and community fundraisers for people having trouble paying their utility bills and for beleaguered local restaurants.

The digital team also made a lot more room for the voice of the audience — and that’s not going to change either. “It’s no longer just a one-way street. It’s a two-way street. And we are encouraging our audience to weigh in on everything,” Polverine says. “People still want to come to us to get the information, but really peppering in what people think and how they feel and what their reaction is has been such a huge part of the content that we do now — just making it more of a conversation. I think that’s one of the big takeaways, too, that our audience is part of what we do.”

Adam Miller says that seeing the talent working from home has also helped bring viewers closer to the newsroom. “That opened up a whole new door in terms of building connections and relationships with our team that you don’t always get behind the anchor desk,” he says. “I think the important thing to do is to pinpoint what about that relationship struck a nerve, what resonated, and build off of that in the months to come.”

Watch a behind-the-scenes video of how WKYC went remote.

But not everything is changing. Mitchell, who anchors the 6 and 11 p.m. newscasts (and serves as executive editor of the late news as well), chose to broadcast from the studio throughout the pandemic — a classic role for an anchor in a time of crisis. “I would argue it offered the viewer not just credibility, but comfort,” Miller says. “And I think that comfort is something Russ could offer that you couldn’t get just anywhere.”

Mitchell, who worked at CBS News for many years (we were colleagues there), is now an evangelist for local news — and can’t wait to get back on the street. “The beauty of local news is getting involved in the community,” he says. “And you can do that via Zoom, you can do that on the telephone, but there’s nothing like getting out there and actually meeting people in person. And I haven’t had a chance to do that in the last year. I hope that comes back in terms of the emotion that television can give to viewers. Only we can do that. TV is still magical.”

Adam Miller uses the same word in agreeing that it’s important to bring back the power of face-to-face interaction, not just on the street but in the newsroom. “It’s the moment when you have that exchange with a colleague, and then suddenly boom — an idea is hatched. That’s where the magic happens.”

So, like many innovation challenges, imagining a post-pandemic future is a balancing act — a matter of preserving what’s best about local broadcast and digital journalism while learning from the crisis to change for the better. “A lot of people look at last year, and it’s been awful,” Jonathan Adkins says. “We’ve all lost loved ones, and those that are close to us. And many of us have been touched in different ways. But for our industry, I’m excited about what can come from this.”

Adam Miller, who returned to his native Cleveland after a successful career at NBC News that started with an internship and culminated in a senior producer job on Today, sees a post-COVID opportunity for local news to play an even bigger part in people’s lives. “Never has there been a story as universal and yet hyperlocal as COVID-19 and the pandemic,” he says. “It has put a spotlight on the importance of local news and reminded people of the power and responsibility that comes with it. I’m hoping, and I believe, that this interest in local news will stay. And as a result, I think we should be offering and could be offering more.”

As for that makeshift control room in Jonathan Adkins’s basement: It’s staying right where it is.

Editor’s note:

If you have a compelling example of COVID-driven innovation that will have a lasting impact on your newsroom, please share it with us at cronkitenewslab@asu.edu. Thanks!