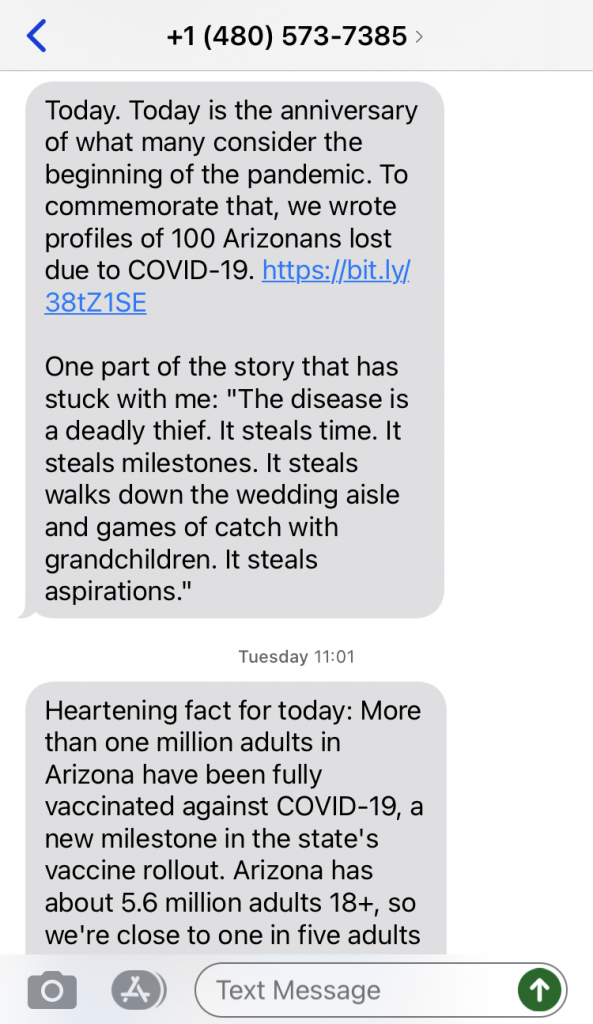

We’ve all relied on our phones over the last isolating, overwhelming year. Some of us text with family. Some text with friends. And here in Arizona, some text with P. Kim Bui, director of audience innovation at The Arizona Republic.

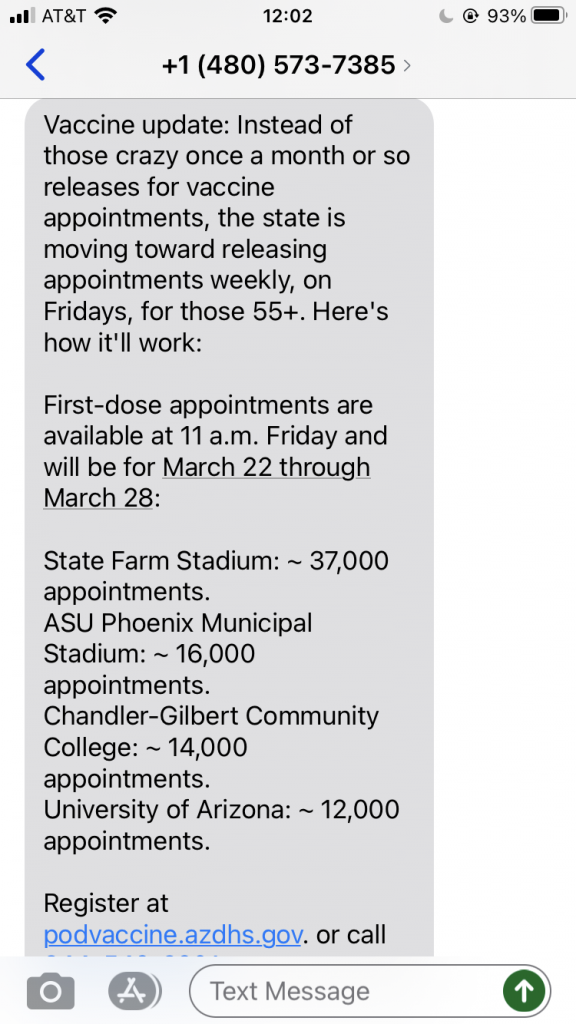

Since last spring, she’s sent messages en masse to anyone who signs up for the latest information on COVID-19. In return, those 3,000 subscribers text her back with their questions, concerns, and photos of the family dog, which she sometimes replies to one-on-one or with another blast.

“People feel like they know me,” says Bui with a laugh. “If I say I’m having a hard day, they’re like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I’m so sorry. What can we do to help?’ I think people are feeling extra lonely. I mean, I’m feeling extra lonely. And any sort of connection you can build during the pandemic is big.”

The tool she’s used to build that connection is Subtext, an SMS messaging platform that lets Bui see all of her replies, but only shows subscribers Bui’s texts and their own. That chance to create a personal, conversational relationship has drawn a variety of users since Subtext launched in 2019 — from chefs and YouTubers to musicians and other news outlets. In addition to The Republic, its journalistic clients have included local organizations like Newsday, The Des Moines Register, and The Austin American-Statesman, as well as national ones like BuzzFeed News, Vanity Fair, and Teen Vogue.

Absent from the list so far? Any local TV stations. “I’ve found it interesting that more radio and TV stations haven’t done this,” says Bui. “Because everyone who’s on-air has a voice already — a really strong voice, compared to a newspaper writer. It’s just training somebody to utilize that voice in a different way.”

At the News Lab, we’re also interested in texting’s potential for TV. We’ve covered Univision 41 Nueva York’s effort to connect with its predominantly Latino audience on the messaging service WhatsApp, as well as a Cronkite News experiment that solicited story ideas on another texting platform called GroundSource. So after reading up on Subtext in a piece by NiemanLab, we wanted to reach out and gauge the opportunity for local stations.

“I think there’s a ton of potential,” says cofounder David Cohn. “Broadcasters already have a sense of personality, right? They’re on TV. There’s a voice and a personality that people associate with and trust. And local topics do really well. Things around local businesses do really well. Local sports, local news and information — civic and politics stuff.”

Bui also sees an audience for TV meteorologists. “The weatherman — like, c’mon! I would love to be on a text thread with a bunch of weather geeks,” she says. “Anything where there’s a niche community or an ongoing issue. Say [you’re] an investigative reporter working on the foster care system, and you want to connect with foster parents and share your work over that. I think it’s particularly useful for beat reporters or anybody who’s working on the same topic for a while.”

With a Subtext combining journalists’ local knowledge and strong voices, Cohn says a TV station could engage more deeply and productively than it does on the major social platforms: “That’s a very noisy space. You have to think about the whole world and trolls, and there’s the algorithm — all of that is gone with texting. You send out a text, and about 80% of people who are going to respond will do so within an hour.”

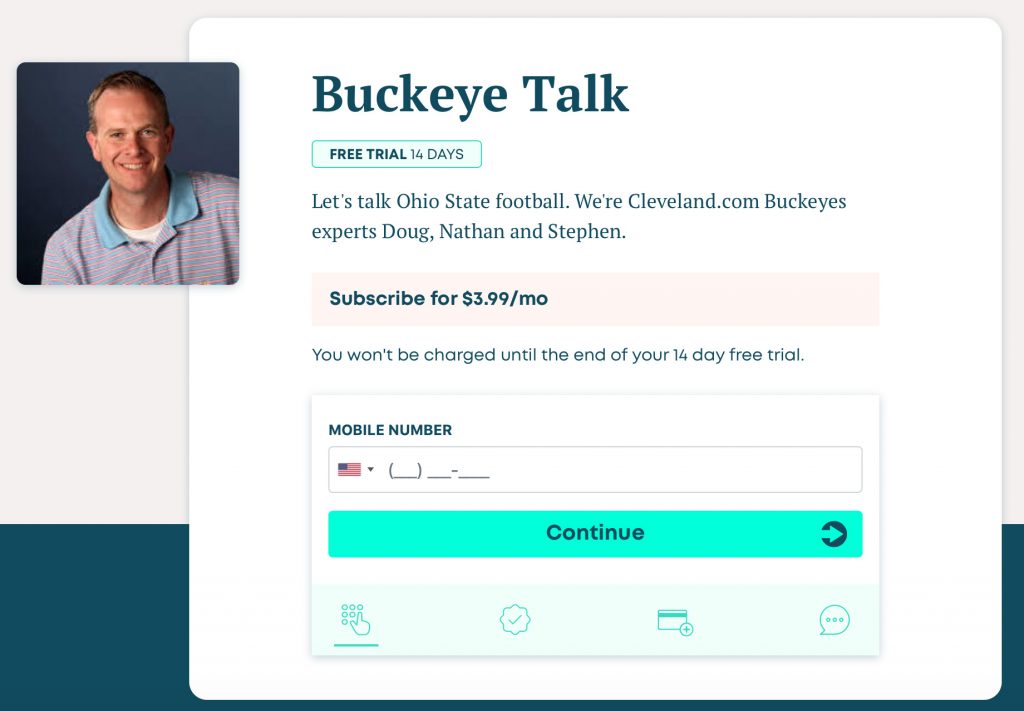

As an example, he points to the text thread for Buckeye Talk, a podcast about Ohio State football hosted by Doug Lesmerises, a sportswriter at Cleveland.com who takes listener questions in every episode.

“Before Subtext, he would do this through Twitter,” says Cohn. “He had like 40,000 followers, and he’d send out a tweet and get like four or five good questions. With a much smaller Subtext audience, he’ll get 50 or 60 good questions, because these are people who get his text — it doesn’t miss them — and who have self-selected or self-identified as super passionate about this. One of them texted back, and he said, ‘Doug, my girlfriend thought you were a friend who just texted me every day about the Buckeyes. I had to tell her what this is and that you’re a reporter.’ That just goes to show the kind of relationship you can build.”

Cohn also makes the argument for Subtext on the metrics and financial fronts. To the first point, he says texting tops social media and email: “Text has a much higher open rate than email — like, 90-plus percent — and a much higher engagement rate. Nobody really responds to email newsletters, but people do respond to text.” And to the second point, he says Subtext doesn’t require web development, making it a faster, more affordable option than building your own app.

For accounts that are free to the public, newsrooms pay Subtext a fee based on the total number of subscribers, but organizations can also monetize and pay for their threads by finding sponsors or setting up subscriptions. “A lot of sports campaigns are subscription,” says Cohn. “People pay $4 or $5 [per month] to get text messages from a local reporter about whatever team they’re passionate about. Those are free [for organizations] to create, and we just do a revenue share.”

P. Kim Bui says The Arizona Republic’s free thread has converted some of its Subtext subscribers into subscribers for the newspaper’s digital content as well. It’s also generated tips and sources for the paper’s health reporters. But its real purpose, she says, is to serve Arizonans with critical COVID-19 updates, cut through the confusion and misinformation in the unending news cycle, and nurture a genuine sense of connection.

“It’s about being a service,” says Bui. “I think that’s what people are really craving and what they’ve really responded to — that we consider this a service. We’re not getting millions of dollars off of it or hundreds of subscriptions. It’s because we see the need, and we want to fill that need as best as we can. And I will say, having been a social media editor, this community we’ve built is more positive and supportive than any other community I’ve worked on.”

With the pandemic ongoing, Bui isn’t sure how long the thread will last. Newsrooms can start and stop their Subtexts whenever they like — and take their subscriber list with them when they go.

But whenever the virus subsides enough that The Republic can phase out its texts, Bui has other ideas for the platform — ideas, she says, that could work for TV stations as well as newspapers. “I think this is a great way to reach people who don’t have a lot of internet access,” she says. “That might be in rural places or on the reservation — or somewhere it’s just a lot easier to send a text than to send somebody to a big database or a website.”

There are other companies that support interaction through text messaging: WKYC in Cleveland is using ZipWhip, for example. Whoever the tech partner may be, if you haven’t tried texting as a supplement to your social media outreach, Bui says it might be worth a look.

“It’s about building loyalty,” she says. “Right now, I’m thinking like, ‘Oh, I haven’t sent a text today. And I didn’t send a text yesterday, because I was off. People are probably wondering where I am.’ And legitimately, that does happen. If I disappear for a couple days, they’ll be like, ‘Where are you? Is this ending? I really need this. Can you help?’ It’s managing a community.”

New expectations for a continuing relationship: a nice “problem” for newsrooms to have. If your newsroom has experimented with texting, we’d like to hear about what you learned. Please let us know at cronkitenewslab@asu.edu.